This week, the European rival to the ADA Scientific Sessions known as EASD (which stands for the European Association for the Study of Diabetes) held its annual meeting, which was the organization's 57th Annual Meeting and it took place virtually (much like the ADA Scientific Sessions did this year) due to COVID-19. EASD was held from September 27, 2021 to October 1, 2021. In recent years, neither the ADA Scientific Sessions not the EASD Meetings have yielded many surprise findings or previously unknown product launches.

My short summary is that Novo Nordisk is finally getting on the "smart pen" cap bandwagon, while rival Lilly cut list prices for insulin lispro by another 40%. Read on for details on both.

A little-noticed news item this year's EASD came from Novo Nordisk, which is a company which has occasionally described itself as a diabetes company but has tried to shift gears and today describes itself as a "Danish multinational pharmaceutical company", and the company's origins were as two of the original licensees to make insulin from the University of Toronto dating back to the 1921 discovery on insulin (Lilly and Sanofi [whose modern day origins were as both Canada's Connaught and Germany's Hoechst] happen to be two others). Truth be told, Novo Nordisk is a company which once dominated the Scandinavian diabetes market, but it has used fat profits generated in the United States to go on a global acquisition binge, eliminating formerly-independent insulin makers in countries such as Brazil (Anyone remember the company known as Biobrás? It disappeared around 2002 when Novo Nordisk bought the company using profits generated in the U.S.).

Incidentally, as hinted, Novo and Nordisk were previously two independent companies who both made insulin, but the two insulin manufacturers merged into a single company back in 1989. Its U.S. presence occurred since the company acquired a joint-venture started back in the early eighties with a U.S. drug company then known as E.R. Squibb & Sons (one of several predecessors to today's Bristol Myers Squibb). Shortly after Novo and Nordisk merged, the company then acquired Squibb's half of the joint venture in 1989 (I'm old enough to remember those origins of the company's relentless acquisition binge).

Anyway, Novo Nordisk is perhaps best known as the company which originated the insulin pen back in the late-1980's. In Europe, most patients prefer using insulin pens, rather than insulin pumps as an insulin delivery mechanism. Aside from not having to wear all the items associated with insulin pumps (infusion sets, a bulky pump generally requiring tubing and batteries, and now, a separate CGM sensor, etc.), insulin pumps are not the worldwide standard of care for autoimmune T1D, rather the insulin pen is in much of the world. But the U.S. is not like the rest of the world; here insulin pens are far less common and also vastly overpriced (as is insulin generally).

Anyway, coinciding with the 2021 EASD meeting, Novo Nordisk announced (see the announcement HERE) a new partnership with a France-based company known as Biocorp which specializes in the design, development, and manufacturing of "innovative medical devices". The Novo Nordisk-Biocorp partnership will reportedly leverage that company's Mallya platform and will be for the Novo Nordisk prefilled pen platform to develop smart insulin pen caps (not too dissimilar from the Bigfoot Unity system).

As part of the partnership deal with Novo Nordisk, Biocorp will receive an upfront payment from Novo Nordisk and different milestone payments are defined staging the partnership's development phase. Upon successful development, Novo Nordisk then plans to distribute the smart pen cap devices in "selected countries", and Biocorp expects to ramp up production volumes from 2022. Most likely, the United States will be excluded from the initial launch, which seems poised to go to Europe first which has a higher incidence of insulin pen users and few patients who struggle to pay for basics such as insulin which have driven many to return to vials and syringes because the cost per unit is lowest that way. Maybe a Novo Nordisk-Biocorp smart pen cap will come to the U.S. and Canada a bit later, once the bugs are worked out. Maybe.

Currently, the number of smart insulin pens is growing on a global basis.

Novo Nordisk has been an outlier by not offering one. Smart insulin pens work with smartphones and enable patients to compute their dosages more accurately, to monitor insulin-on-board (IOB), and to automatically track their dose logging, all of which have traditionally been absent in patients treated with multiple daily injections (MDI). San Diego-based Companion Medical (which was acquired by Medtronic diabetes in August 2020) offers one smart pen called InPen.

InPen uses insulin cartridges which are another Novo Nordisk invention. But many U.S. patients struggle with pens/cartridges because while their insurance may pay for the InPen itself, their insurance pharmacy benefits sometimes will not cover the more costly insulin pen cartridges, which makes no sense. But pharmacy benefits in the U.S. no longer make sense anyway when more than half of all plans have high-deductibles.

Novo Nordisk's affordability option (which was copied from Lilly, which innovated it) - an "authorized generic" or "authorized biosimilar" branded as Novo Nordisk Insulin Aspart https://www.nnpi.com/ may assist on that because it assuredly is less costly and readily-available, but is not widely known about, but Lilly's cheaper Lilly Insulin Lispro https://www.lillyinsulinlispro.com/ option does not include insulin pen cartridges --- in the U.S., pen cartridges are a bit of an anomaly. Lilly does makes them for Humalog, but Sanofi doesn't sell pen cartridges for either its own rapid-acting analogue Apidra nor the biosimilar Admelog. Pen cartridges are more of a Novo Nordisk thing. Given that much of Lilly's sales growth is in the less-heavily rebated insulin variety, maybe that will change, but I wouldn't bet on it.

A slightly newer smart pen offering is Bigfoot Biomedical's Unity smart pen cap system, which was the company's first-ever FDA approved medical device which is unique in that it works with the Abbott Freestyle Libre 2 flash glucose monitoring device (rather than Dexcom), tying the disparate pieces together into a seamless system which works nicely and adds features not present in the existing devices, such as automatic CGM readings, sharing and low blood glucose alarms that American CGM users have come to expect as core CGM features.

Bigfoot has a rather peculiar distribution system which is currently merchandised through something called the Bigfoot Clinic Hub, which an endocrinologist must subscribe to. But many endocrinologists which are part of large group medical practices (increasingly, many are owned by hospital chains) are effectively locked out of offering Bigfoot Unity to their patients. I think Bigfoot's Clinic Hub is an effort by the company to establish widespread relationships with endos treating diabetes so that when the company's bigger and more expensive smart insulin pump system launches, so they will have established doctor relationships which will help them sell their other products. Right now, those relationships are few in number so it is impossible to simply buy a Bigfoot Unity smart insulin pen cap. Whether that changes over time remains to be seen.

But Europe is not like the U.S., and universal healthcare coverage is the general rule across the European continent. Patients in Europe generally don't struggle to get coverage of basic necessities like insulin as they often do in the United States, they just walk into the pharmacy and pick it up when needed, often free or a rather marginal cost. By comparison, in the convoluted U.S. market, patients walk into a pharmacy and may be charged more than $300 for a 10 ml vial of insulin, which is insane and has resulted in one in four patients with insulin-requiring diabetes to ration insulin. Its as if the U.S. is like a third-world country where patients struggle to attain adequate medical care.

The Novo Nordisk-Bicorp deal has potential to add the benefit of smart insulin pen dosing and tracking of IOB and dosage tracking to Novo Nordisk's no-longer-so-innovative prefilled insulin pens, and it could result in lower costs since Novo Nordisk mass-merchandises insulin pens on a worldwide basis. So Novo Nordisk is developing smarter insulin pen caps.

Meanwhile, recall that in 2018, Lilly announced what it's calling the Lilly Cambridge Innovation Center located in the biotech hub of Cambridge, Massachusetts (it is located in Kendall Square, in the footsteps of Massachusetts Institute of Technology/MIT and just 2 subway stops on the MBTA Red Line away from Harvard University) to develop what it calls a "Connected Diabetes Ecosystem" (or "CDE") featuring either a closed-loop system using either an insulin pump or smart pen, integrated CGM and/or blood glucose meters, a smart dosing/control algorithm, and a robust smartphone app to tie the pieces together.

Diabetes Mine covered that at https://www.healthline.com/diabetesmine/lilly-diabetes-blogger-summit-2018. So far, patients haven't seen much come from that yet, but perhaps the Novo Nordisk deal with Biocorp is an effort to play catch-up since the Danish company's insulin pens may be widely-used, but are assuredly not "smart" pens -- the current Novo Nordisk FlexPens are actually rather stupid devices right now.

Perhaps also timed to deliver a slap in the face to its biggest insulin making rival, Eli Lilly & Company made another big announcement (maybe to steal Novo Nordisk's thunder) during the EASD. Remember when Novo Nordisk announced a deal with Walmart to sell a less costly co-branded version of Novolog at Walmart pharmacies at a discounted price, just as the ADA Scientific Sessions was closing? Lilly's announcement seems to be meant to steal some thunder from its Danish insulin-making rival just as the Novo Nordisk-Relion Novolog announcement made earlier this summer at the ADA did.

Lilly, like Novo Nordisk and Sanofi, has been on the hot-seat for much of the past decade over runaway U.S. insulin prices, so it did something a bit unexpected during EASD: it announced it would be further reducing the list price of Lilly Insulin Lispro Injection by another 40%, which is the "authorized generic" version of the company's now out-of-patent Humalog, the rapid-acting insulin analogue which has since been one-upped by the company's marginally-faster (and still patent-protected) Lyumjev insulin. When the less costly product launched in 2020, it was widely promoted as being a half-priced Humalog at the time. Lilly’s press release revealed “Approximately 1 in 3 prescriptions for Lilly's U-100 mealtime insulin – Lilly's most commonly used insulin formulation – is for Insulin Lispro Injection.”

In 2020, Lilly introduced its "authorized generic" version of Humalog as a new affordability option. When it launched, the press quickly called it "half-priced" Humalog because the bogus list price was half of what brand-name Humalog sold for. Savvy patients quickly discovered that "half-price" was also bogus; they could get vials (or prefilled pens) of Lilly Insulin Lispro for about 75% less than brand-name Humalog by using a readily-available GoodRx coupon (or from several rival Rx coupon-generating apps). The Lilly deal worked so well that Novo Nordisk quickly copied it, launching its own authorized generic/biosimilar of insulin aspart.

Lilly's marginally faster version of Humalog branded as Lyumjev is still trying to build awareness and a customer base (and is still patent-protected, unlike Humalog), much as Danish rival Novo Nordisk has started doing since it launched Fiasp (a name derived from F aster I nsulin ASP art) in 2017. Neither Fiasp nor Lyumjev are very big right now, but the companies are widely expected to simply stop making the older products and replace them with the newer, slightly faster versions instead, leaving biosimilar makers to fight amongst themselves for selling less costly, slightly older, un-patentented insulin varieties.

Those newer products seem poised to replace the slightly older (and now out-of-patent) rapid acting insulin analogues -- and if history is any indication, the companies may ultimately just stop making the older varieties -- effectively "retiring" them just as they previously did with Iletin as well as the entire biosynthetic "human" Lente series: Humulin S, Humulin L, Humulin U. It wasn't that patients weren't using those products. Its just that Lilly had invested millions in its Genentech biosynthetic "human" insulin varieties, so they decided to retire the old product lines and FORCE patients to use the newer, more costly patent-protected products instead.

Humalog is still the real Lilly insulin blockbuster, but its patents have all expired or will expire soon, and more biosimilars may be coming before long. There is already a biosimilar of Humalog made by Sanofi branded as Admelog on the market, but it is very expensive and sales are declining as a result of its price. Currently, I'm not aware of any other biosimilars of lispro and I'm also not aware of any currently in development.

But right now, there are at least two or three biosimilars of Novolog (aspart) in development from Viatris/Biocon, Lannett/HEC. Sanofi also makes one sold in Europe, but that company has been non-committal about introducing it in the U.S. because sales of its Humalog biosimilar branded as Admelog have evaporated into thin air because it is actually more expensive than Lilly's Insulin Lispro is. Right now, even with a manufacturer discount coupon from Sanofi applicable to Admelog, the lowest cost for Sanofi Admelog (U-100 insulin lispro rDNA origin) is $99/vial. But Lilly Insulin Lispro can be bought for just $48.85/vial at CVS Pharmacies nationwide using a GoodRx coupon, which is about half the price of Sanofi's biosimilar. This is another manifestation of what Wall Street refers to as "rebate walls" drug companies use to eliminate or inhibit potential competitors. Whether it is accomplished with coupons, or secretive rebates paid to insurance company-owned PBM's, the impact is that it is anti-competitive, and it is very likely illegal.

But for Lilly, its sales numbers do not lie. Heavily-rebated brand-name Humalog are slowing, while the "authorized biosimilar" branded as Lilly Insulin Lispo are more than making up for it. Hence, the company announced during EASD that it would be further reducing the price of the authorized biosimilar Lilly Insulin Lispro by another 40% starting in January 2022. (see the press release HERE -- that could potentially force Novo Nordisk to do the same. It is also less difficult for Lilly execs to simply bypass the whole Rx rebate mess. They won't need a sales staff dedicated to selling to PBM's and insurance company formulary managers. Landing one is still a big boost to sales, so it may continue, but it may not be Lilly's sole marketing focus anymore since it can still generate sales growth without landing a big insurance company/PBM formulary.

The move makes sense financially for Lilly. In Lilly's Q2 2021 investor earnings presentation, Lilly revealed that while sales of Humalog had increased 9% on a worldwide basis compared to Q2 2020, sales of its heavily-rebated (to PBM's) brand-name Humalog had actually fallen, yet Lilly Insulin Lispro sales had grown, resulting in the company's workhorse rapid-acting insulin analogue Humalog sales growing slightly year-over-year. Sales of its new-and-improved Lyumjev were still too small to impact the bottom line in a meaningful way.

For Lilly, just maybe, the ever-higher insulin rebates needed to "bribe" (secure) commercial healthcare insurance company formulary placement might be a huge waste of corporate cash. After all, Novo Nordisk now admits that it is paying 74% of the company's gross sales as rebates paid to PBM's. Lilly's sales numbers for Humalog suggest that it might just be working. If so, it has potential to alter the rebate-driven U.S. insulin market as we currently know it.

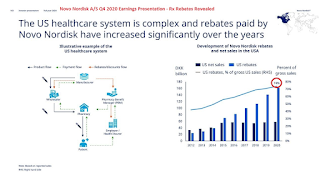

During Q3 2020, the Novo Nordisk rebate figure paid to bribe, err...I mean to secure, commercial healthcare insurance company formulary placement was 71%. The next quarter, the rebate figure was up another 3% totaling 74% of Novo Nordisk's gross insulin sales.

Prior to that, the company tried to keep the Rx rebate figure a secret, but investors kept asking the company about it. In fact, in 2017, Novo Nordisk shareholders sued the company saying company management mislead them on the magnitude of its pricing pressures. In a court filing, the plaintiffs of the shareholder lawsuit said that while other companies told investors that their insulin-related revenues would diminish as a result of pricing pressures, Novo Nordisk executives falsely assured investors that "the company was not subject to the same pressures and that its sales and profits would continue to grow". That was a lie. Evidently, the pricing pressures for Novo Nordisk were exactly the same as its competitors faced. The company's CEO at the time, Lars Rebien Sørensen, uncharacteristically "retired early". Perhaps not coincidentally, just this week, Novo Nordisk agreed to settle the lawsuit with shareholders to the tune of $100 million (to be paid for by insurance).

Novo Nordisk is Addicted to U.S. Rebates Paid to PBM's to Drive Sales, But Rebates Are Also Driving Its Profits Way Down

Nevertheless, Novo Nordisk has steadily continued increasing rebates, quarter-after-quarter. As noted, the company has increased the percentage about 3% each quarter. That is the only way Novo Nordisk insulin sales in the U.S. have grown.

But to what end?

PBM appetite for rebates is endless. Will Novo Nordisk stop when they are giving PBM's 99% of their sales as rebates? 100%? That indeed explains why the company has shifted almost entirely to GLP-1 inhibitors for Type 2 diabetes which now drives virtually all of the company's revenues now.

Lilly seems to be concluding that maybe its best option is to shift away from the rebate-driven sales model.

I also believe that Lilly sees potential legal troubles ahead on the hidden rebates paid to insurance company owned pharmacy benefits managers ("PBM's"). There is no secret that PBM rebates are on the Federal Trade Commission's ("FTC") radar. So far, each of the public FTC meetings over the past few months have featured a steady number of independent pharmacy owners complaining about PBM's contract abuse, and more recently, patients alike have testified, decrying that their insulin prices are growing, not falling, in spite of bogus PBM assertions of how much savings they generate. The FTC was recently asked by Congress to look into PBM "rebate walls" and the FTC issued a terse "report" https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-report-rebate-walls/federal_trade_commission_report_on_rebate_walls_.pdf which really looked more like a promise to examine the anti-competitive PBM practices.

FTC commissioners have finally promised to investigate the "rebate wall" matter further. Several FTC commissioners have opined on the matter, including FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-report-rebate-walls/federal_trade_commission_report_on_rebate_walls_.pdf and FTC Acting Acting Chairwoman Rebecca Kelly Slaughter https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/1590532/statement_of_acting_chairwoman_slaughter_regarding_the_ftc_rebate_wall_report_to_congress.pdf.

The roots to all of it is the nonsense PBM's have been getting away with by keeping what they do a secret, but it looks to be illegal. But the key unanswered question is when the U.S. Federal Trade Commission will finally begin suing the pharmaceutical industry and the PBM's for illegal "tying"? I suggested that needs to happen in September 2021. It seems pretty clear that a case likely exists, the question becomes when they will begin prosecution. It is for that reason that I think Lilly may finally be realizing rebates paid to PBM's are criminal and could get the company into trouble if FTC were to sue Lilly. That said, Novo Nordisk is full speed ahead on rebates, but it may be forced reconsider in light of what Lilly is now doing. Every time an insurance plan favors a branded drug (with a rebate) over an identical "authorized" generic/biosimilar (without rebate), it's looks to be a bribe that might be in violation of:

- Clayton Act Sec. 3 (exclusionary rebates)

- Sherman Act, Sec. 1 (exclusionary rebates)

- Rob. Patman Act

- Anti-Kickback Statute

- ERISA

Now the question is when the FTC finally start filing lawsuits?! I think we can expect the FTC to conduct some research into the matter (it is well-equipped to do so) so that new Biden FTC leadership means that the Trump FTC commissioners are outnumbered and have consistently lost on key FTC procedural votes. Let's hope FTC acts relatively quickly, but collects enough data to actually implement long-overdue changes to the way prescription drugs in the U.S. are merchandised and sold.

No comments:

Post a Comment